Prevalence of Malnutrition and Stunting in Under Five Creche of a Rural Private School in Owerri North, Imo State

Abstract

The prevalence of malnutrition and stunting in under five Creche of any rural private school in Owerri North L. G. A was investigated. Owerri North is made up of seven districts namely Egbu, Emekuku, Emii, Ihitte/Ogada/Oha, Naze, Obibi-Uratta and Orji. A random selection of four schools were made and the schools include; Oxford Foundation Academy, Ulakwo, Rhema Kiddies School, Amaorie, Noble Star Academy, Orji and St. Carols Nursery and Primary School, Ulakwo. These schools were selected because they meet the set out standard and quality for Nursery Education. The study adopted a cross-sectional design involving 250 pupils from four schools. Simple random selection by balloting was used to select the children from the schools. The questionnaire was validated and pre-tested by lecturers in the Nutrition and Dietetics Department, and data on anthropometric indices- weight and height, BMI and MUAC; socio-demographic status, dietary pattern and frequency of food consumption were collected. Results obtained showed that one hundred and twelve (44.8%) under five were males while 138 were females (55.2%). About 209 (83.6%) were from Imo state and of the Igbo ethnic group240 (96%). Five (2%) of the respondents were between the ages of 6 to 12 months, 114 (45.6%) were aged between 1 to 3 years, and 130 (52%) were aged 3 to 5 years. The socio-demographic data of the respondents showed that the 70 (28%) of the respondents’ fathers were civil servant, 94 (37.6%) were traders and 27 (10.8%) were farmers. Fifty (20%) of the respondents’ mothers were civil servants, 134 (53.6%) were traders and 25 (10%) were farmers, while 41 (16.4%) were of other occupations. Monthly income distribution of the children’s parents showed that 29 (11.6%) earned ₦10,000-50,000, 119 (47.6%) earned ₦50,000 – 100,000, 96 (38.4%) earned above ₦100,000. Data from living condition showed that 154 (61.6%) live in a bedroom flat, 44 (17.6%) live in one room apartment and 39 (15.6%) live in public yard. Data on the dietary practices of the children’s care givers showed 221 (88.4%) prepared food at home to feed the children, (78.4%) eat three times in a day, 214 (85.6%) took in-between meals and 173 (69.2%) took snacks as in-between meals. About 243 (97.2%) consumed fruits and vegetables, of which (55.2%) were frequent, 66 (26.4%) twice in a week and 36 (14.4%) occasionally. Data from the frequency of food consumption from various food groups showed that 97 (38.8%) of the children consumed cereals and their products on a daily basis, 92 (36.8%) consumed cereals 3 to 4 times in a week. Starchy roots and tubers consumption showed that 98 (39.2%) consumed roots and tubers three to four times weekly, 88 (35.2%) once to twice weekly. One hundred and seven (42.8%) consumed legumes and its products once to twice weekly, 83 (33.2%) three to four times weekly, while 119 (47.6%) consumed vegetables daily, and 82 (32.8%) consumed fruits once to twice per week with additional 79 (31.6%) daily. Data on milk and milk products consumption showed that 92 (36.8%) consumed milk three to four times weekly and 62 (24.8%) daily. The prevalence of wasting among the under-five was 2.8%, stunting 3.2%, and underweight was 1.6%. The mid-upper arm circumference measurement showed that only 3 (1.2%) of the children were malnourished, while 242 (96.8%) were normal. This study shows that stunting, underweight and wasting results from a complex interaction of factors. Poor Socioeconomic and environmental conditions are important determinants of nutritional status. Poor nutrition knowledge as a re3sult of limited access to nutrition education also leads to poor food choice by the mothers. Therefore, education of women should be treated with utmost priority because it will help raise the standard of living of the family and pave way for a better socio-economic status and healthier food choice.

Keyword: Anthropometric indices; Feeding habit; Health; Nutritional status; Private schools; Nigeria

Introduction

The concept of malnutrition and stunting in under five kids is not foreign to the ear. Theoretically, malnutrition is a term that refers to both under nutrition and over nutrition. People are malnourished if the calories and protein they take through their diet are not sufficient for their growth and maintenance due to ill health, they are not able to make complete use of the food they eat (under nutrition) or if they consume too many calories (over nutrition). In this paper, we consider under nutrition and malnutrition equivalently [1]. The physical and /or mental development of children can be hampered by poor nutrition during childhood which consequently may lead to a greater risk of casualty from communicable diseases or additional critical infection which ultimately end in a bigger economic burden of a society. Evidently, malnutrition among children and mothers adversely affect the growth of development in both national and international economic arena as well as health and sustainable developments. Malnutrition is the salient source of 3.5 million deaths globally and responsible for 35% of the morbidities among children under five which undoubtedly, defines malnutrition as a prime cause for critical health and development disorders faced by people, mostly children in developing countries Characteristics of children suffering from malnutrition include stunting or chronic malnutrition (low height for age), wasting or acute malnutrition (low weight fit height ) or being underweight for their age (United Nations 4th report ,2000). Stunting is the impaired growth and development that children experience from poor nutrition, repeated infection, and inadequate psychosocial stimulation. Children are defined as stunted if their height -for-age is more than two standard deviations below the WHO Child Growth Standards median (WHO, 2019).

Many of us use the words Daycare, Crèche, Educare, Nursery school and Pre-primary fairly interchangeably. However, some mother’s become quite upset when they realise the type of care their toddler or pre- schooler is receiving is not what they had been expecting. A crèche or day care facility offers supervised play for babies and young toddlers. The staff may have certificates in childcare but won’t necessarily have degrees in early childhood development. There are toys and lots of fun and the needs of your child is being taken care of with meal, snacks, naps, changing times and some even do potty training at a set stage (though there is much debate around this ,as many believe that potty training when children are ready is more successful) [2].

Globally, prevalence of stunning amongst school age children typically varies from place to place ranging from 9.3-24.0% in Latin America and Carribean to as high as 20.2-48.1 in Africa. In South Africa the prevalence for stunting is 18.0% whereas it is as high as 42.0% and 50.0% in mid and Eastern Africa respectively. Nationally, prevalence of stunting among primary school children ranges from 11.5% in Anambra, 11.8% in Onitsha to as high as 60% in Kebbi State. In Nigeria, the progress towards halving the proportion of people suffering from hunger under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) has hitherto been slow and daunting. Stunting has profound effects on the health of children. It predisposes to heightened risks of severe infection as a result of immune compromised responses. Stunting has also been implicated in increased morbidity and mortality, reduced physical, neurodevelopmental and economic capacity and an elevated risk of metabolic diseases diseases adulthood. Under nutrition significantly interferes with a number of bodily functioned such as immunity (cell -mediated immune responses) antibody responses and cytokine production that as a result provoke poor health outcomes in early infancy and childhood. Most importantly, the high prevalence of bacterial and parasitic diseases in poor and developing countries have continued of exacerbate the effect of stunting in children.

Risks of stunting are high in children as a result of heightened vulnerabilities to low dietary intake, inaccessibility to food, inequitable distribution of food within the household, improper food storage and preparation, dietary taboos and infectious diseases. Significant associations have been established between early childhood stunting and late onset adulthood depression with elevated self - reported conduct problems. The consequences of stunting iterated above demonstrate the need to investigate and implement interventions to address the problem amongst school children. Furthermore, the ‘double burden of malnutrition’, (in which households have a stunted child and an overweight mother) makes stunting as a form of under nutrition quite worrisome. Numerous studies have investigated and provided broader national estimates of stunting, even though key health-related targets in the Millennium Development Goals and the Sustainable Development Goals supports concerted calls to eradicate poverty and hunger whilst also bridging inequities in health. Bearing this in mind, there is a dire need for comparative statistics across wealth quintiles and vulnerable populations that can inform formulation and adoption of feasible policies at the strategic and operational levels of government in order to curtail the effects of stunting in Nigeria. The prevalence of malnutrition and stunting occurs mainly in children especially the under five. In Nigeria, the economic situation of the country has led to malnutrition and stunting. Hence, the knowledge of the effects of malnutrition will aid in the consumption of adequate diet to increase the healthiness of the population. It was therefore important to study how malnutrition affects the health of an individual and may lead to chronic health effect. The general objective of the study is to examine the prevalence of malnutrition and stunting in Under five (5) creche in rural private Nursery Schools in Owerri North L.G.A.

The benefits that could be deprived from the outcome of the research work are as follows:

1. Identification of the causes of poor nutrition on children and the implementation of the recommendation suggestions by various nutritional bodied which will lead to better and healthy generation,

2. Provides useful information on the alarming rate of malnutrition in the country and how it will be reduced and

3. The result of the work can be used as models by government and all health workers on child right and wellbeing.

Materials and methods

Study area

Owerri is located within the Southeast Part of Nigeria and lies at Latitude 50 27-50 31’N and longitude 6055-7003’E, it is the capital of Imo State. Owerri North is made up of seven districts namely Egbu, Emekuku, Emii, Ihitte/Ogada/Oha, Naze, Obibi-Uratta and Orji. The 12 wards in Owerri North L.G.A are Agbala/Obube/ Ulakwo, Awaka/Ihitte Ogada, Egbu, Emekuku i, Emekuku ii, Emii, Ihitte Oha, Naze, Obiibi Uratta I, Obiibi Uratta ii, Obibiezena, Orji. A random selection of four schools were made and the schools include; Oxford Foundation Academy, Ulakwo, Rhema Kiddies School, Amaorie, Noble Star Academy, Orji and St. Carols Nursery and Primary School, Ulakwo. These schools were selected because they meet the set out standard and quality for Nursery Education.

Survey design

A cross sectional study of 250 pupils from four schools.

Sample selection

Simple random selection by balloting was used to select the children from the schools.

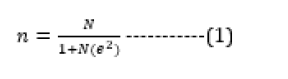

Sample size determination

The formula of YaroYahmen (1974) as presented in equation (1) was used for the samples size determination.

Where n = sample size; N = population size = 100; 1 = constant; e= margin of error (5% or 0.05) and by solving the equation (1), N = 518 and from calculation, n = 250

Data collection

The instruments used include;

Questionnaire: The questionnaire was validated and pre-tested by lecturers in the Nutrition and Dietetics Department, it was done for reliability and validity of the study. The questionnaire was made to pass round and get to every child, taken home to be filled by their parents or caregiver then returned the next day. I took their anthropometric measurement before the questionnaires were taken home.

Anthropometry: Anthropometric measurement and BMI of each child was calculated.

Height measurement: The height was measured barefooted to the nearest 0.01m, a standard deliberate stadiometer was used with the subject (child), standing erect and the feet parallel and held buttocks, shoulders and back of the child upright. Then with the head held comfortably erect with both hands hanging by the side.

Body Mass Index (BMI): BMI is a number that associates a person’s weight with his or her height/length. The formula used to calculate BMI is as follows: weight in kg divided by length in metres squared (Weight in kg ÷ height in metres m²). A BMI over 18.5 indicates adequate nutrition; below 16 is an indication of energy deficiency, BMI between 25 and 30 indicates over nutrition, whereas >30 BMI indicate obesity. The weight categories for children are defined as follows; Under weight is BMI of less than the 5th percentile ; Normal weight is a BMI from the 5th percentile to below the 85th percentile; Overweight is a BMI above the 85th percentile to below the 95th percentile and Obese is a BMI greater than or equal to the 95th percentile.

Mid Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC): The MUAC gives an indication of the degree of wasting and stunting and is a good predicator of mortality. Research shows that it is equally good, than other measurement for screening young children. The MUAC was measured using a MUAC tape. MUAC is the circumference of the left upper arm and is measured at the midpoint between the tip of the shoulder and elbow.

Data analysis

The data was collected according to the children’s age. Weight and height parameters was used to obtain their BMI; Statistical package for social science version 20.0 was used. Frequency and percentage was also used.

Statistical analysis

Statistical package for social sciences was used to analyse the data. Descriptive statistic including frequencies and percentage was used to analyse socio economic data and standard deviation was used to analyse anthropometry measurement of the children.

Results

Personal data of the under five

Table 1 showed the personal data of the under-five. One hundred and twelve (44.8%) under five were males while 138 were females (55.2%). About 209 (83.6%) were from Imo state while 41 (16.4%) were from other states of the country. Majority 240 (96%) were of the Igbo ethnic group, 1 (0.4%) Yoruba, and 4 (1.6%) Hausa. Five (2%) of the respondents were between the ages of 6 to 12 months, 114 (45.6%) were aged between 1 to 3 years, and 130 (52%) were aged 3 to 5 years (Table 1).

Socio-demographic data of the respondents

The socio-demographic data of the respondents showed that the 70 (28%) of the respondents’ fathers were civil servant, 94 (37.6%) were traders and 27 (10.8%) were farmers. Fifty (20%) of the respondents’ mothers were civil servants, 134 (53.6%) were traders and 25 (10%) were farmers, while 41 (16.4%) were of other occupations. Monthly income distribution of the children’s parents showed that 29 (11.6%) earned ₦10,000 – 50,000, 119 (47.6%) earned ₦50,000 – 100,000, 96 (38.4%) earned above ₦100,000, while only 6 (2.4%) earned a million plus. Data on the number of siblings the children have showed that 17 (6.8%) have one, 55 (22.0) have two, 92 (36.8%) have three, while others 86 (34.4%) have more than three. Data from living condition showed that 154 (61.6%) live in a bedroom flat, 44 (17.6%) live in one room apartment, 39 (15.6%) live in public yard, and 13 (5.2%) live in other kind of houses (Table 2).

Dietary practices of the respondents

Data on the dietary practices of the children’s care givers showed 221 (88.4%) prepared food at home to feed the children, while 29 (11.6%) purchased food outside the home. Majority of the children (78.4%) eat three times in a day, 15 (6.0%) eat twice daily, only 9 (3.6%) eat once in a day and 30 (12.0%) eat more than three times per day. Two hundred and fourteen (85.6%) took in-between meals, while 36 (14.4%) did not. Data on the choice of in-between meals showed that 173 (69.2%) took snacks, 28 (11.2%) took beverages, 22 (8.8%) took a full course meal, while 27 (10.8%) took other things as in-between meals. About 243 (97.2%) consumed fruits and vegetables, and 7 (2.8%) did not. One hundred and thirty eight (55.2%) consumed fruits and vegetables frequently, 66 (26.4%) twice in a week, 36 (14.4%) occasionally and 7 (2.8%) rarely (Table 3).

Food frequency of the respondents

Data from the frequency of food consumption from various food groups showed that 97 (38.8%) of the children consumed cereals and their products on a daily basis, 92 (36.8%) consumed cereals 3 to 4 times in a week, 33 (13.2%) once to twice weekly, 20 (8.0%) twice to three times monthly, and only 8 (3.2%) once in a month. Starchy roots and tubers consumption showed that 98 (39.2%) consumed roots and tubers three to four times weekly, 88 (35.2%) once to twice weekly, 48 (19.2%) daily, 11 (4.4%) two to three times per month. One hundred and seven (42.8%) consumed legumes and its products once to twice weekly, 83 (33.2%) three to four times weekly, 27 (10.8%) daily, 19 (7.6%) two to three times per month, and 14 (5.6%) once in a month. Data on vegetables consumption showed that 119 (47.6%) consumed vegetables daily, 72 (28%) three to four times weekly, 35 (14%) once to twice weekly, 14 (5.6%) two to three times per month, while only 10 (4.0) consumed vegetables once in a month. Eighty two (32.8%) consumed fruits once to twice per week, 79 (31.6%) daily, 59 (23.6%) three to four times per week, 23 (9.2%) twice to thrice monthly, and only 7 (2.8%) once in a month. 96 (38.4%) of the children consumed nuts and seeds two to three times monthly, 74 (29.6%) consumed one to two times in a week, 37 (14.8%) three to four times weekly, 23 (9.2%) twice to three times, and only 20 (8.0%) daily. Eggs, meat and poultry consumption showed that 95 (38%) consumed eggs, meat and poultry three to four times weekly, 93 (37.2%) daily, 48 (19.2%) 0nce to twice weekly, 11 (4.4%) two to three times per month and 3 (1.2%) once in a month. Eighty seven (34.8%) consumed beverages daily, 84 (33.6%) three to four times weekly, 54 (21.6%) one to two times weekly, 13 (5.2%) two to three times per month, and 12 (4.8%) once in a month. Data on milk and milk products consumption showed that 92 (36.8%) consumed vegetables three to four times weekly, 62 (24.8%) daily, 41 (16.4%) once to twice weekly, 33 (13.2%) two to three times per month, while only 22 (8.8%) consumed milk and milk products once in a month (Table 4).

Nutritional status of the under 5 children by sex

Table 5 showed the nutritional status of the under-five children. The weight for age of the children showed that 7 (2.8%) were wasted, 175 (70.0%) were normal or at low risk and 68 (27.2%) were slightly above normal. The height – for – age, status showed that 8 (3.2%) were stunted, 192 (76.8%) were normal or at low risk, while 50 (20%) were above normal. For weight for age, 4 (1.6%) were underweight, 200 (80.0%) were normal or at low risk, while 46 (18.4%) were above normal. The mid-upper arm circumference measurement showed that only 3 (1.2%) of the children were malnourished, 5 (2.05%) were at risk, while 242 (96.8%) were normal (Table 5).

Table 6 presents the mean and standard deviation for anthropometric measurements of the children. The mean height of the under-five children was 1.02±0.09 for the males and 1.02±0.08 for the females. The mean weight of the under-five children was 16.51±3.48 for the males and 17.01±2.79 for the females. The mean mid-upper arm circumference of the under-five was 15.15±2.12 for the males and 15.36±1.87 for the females (Table 6).

Discussion

Personal and socio-demographic data of the under five

Data obtained from the research showed that children aged 6 to 59 months were studied, of which 112 (44.8%) were males while 138 (55.2%) were females. Majority, 209 (83.6), of the respondents were indigenes of Imo State where the study was carried out and are Igbos 240 (96.0%). A greater percentage of the respondents aged 3 to 5 years 130 (52.0%). About 37.6% of the respondents fathers were traders, 28% were civil servants and 23.6% represented other occupational distribution. The high percentage of traders in the study revealed that trading is the major occupation of the fathers in the geographical location of the study. Similar trend was repeated among mothers of which 53.6% where traders, and 20% were civil servants. According to Mosley and Chen (2014) [3], maternal education affects children’s health and nutritional outcomes through its effect on improving women’s socioeconomic status. A higher level of maternal education leads to increased knowledge about health and nutrition, which, in turn, leads to an increase in the quality of the diets consumed by children [4]. If maternal education is to play a significant role in reducing child malnutrition, women need to be educated beyond the primary school level. Monthly income distribution of the respondents’ parents showed that a greater percentage earned between ₦50,000-100,000 which corresponds with recent study by Olodu et al. (2019) [5] on a higher monthly income more than ₦20,000, while 38.4% earned above ₦100,000. This is in accordance with reports by Mathieson and Koller, (2016) [6] who stated that healthy eating habits are largely determined by social, economic and cultural factors (such as place of residents) that influence access, availability and uptake. The number of siblings the respondents had gave a little insight on the probable family size of the respondents. Smaller family sizes (one 6.8%, two 22.0% and three 36.8% siblings) could be exposed to better care and access to healthy foods and adequate diet which can promote good health and reduce risk of diseases [5]. More than half (61.6%) of the respondents live in better houses which indicates good hygiene and sanitation, better living conditions and less overcrowding. Akombi et al. (2017) [7] reported that children from poor households are at a greater risk of being stunted and severely stunted than children from richer households. This may be attributed to the fact that with less income to spend on proper nutrition, children from underprivileged households are more prone to growth failure due to in-sufficient food intake, higher risk of infection as well as lack of access to basic health care services. Present study is supported by a study carried out in Zambia where children from poorer households reported a lower nutritional status than those from richer households [8]. Therefore, to improve child health in poor households, an establishment of properly functioning economic and financial structures which supports children from underprivileged households is needed so as to improve food security and access to basic health care services. The child’s well-being is affected by his/ her environment (including the home) which is largely influenced by the family structure, composition and relationship to members in the household [9].

According to WHO (2018) [10], Brazil experienced a sharp reduction of socioeconomic inequalities from 1996 to 2007 which resulted in child stunting dropping from 37% in 1974 to 7% in 2006–2007. Two thirds of the decline could be attributed to improvements in maternal schooling, family purchasing power, maternal and child health care, and coverage of water supply and sanitation services [11]. More girls were enrolled in and completed primary school in the 1990s which increased overall maternal schooling in adulthood. As a result of the education received, the women also had fewer children. The purchasing power of, and the minimum wage received by, unskilled workers increased, unemployment decreased, and cash transfer programmes for low-income families were expanded. Sanitation services also increased and severe food insecurity was reduced by 27% between 2004 and 2006–2007. Thus, income redistribution and universal access to education, health, water supply and sanitation services impacted child nutrition [11].

Dietary practices of the respondents

Data on the dietary practices of the children’s care givers showed 221 (88.4%) prepared food at home to feed the children, while 29 (11.6%) purchased food outside the home. Food is the fuel necessary to get through a normal day. Calories in food provide energy to carry out regular day-to-day activities. Without an adequate amount of this energy, pupils may fall asleep in school or lack the energy to pay attention to an entire day of classes [12]. Home prepared meals are better and more hygienic for a growing child since adequate food condiments are added and there is a regulated rate of seasoning and processed ingredients going into the food [12]. It is also healthier and cheaper than purchased meals from fast foods. Greater percentage (78.4%) of the respondents observed the routine three square meal per day, while 12.0% east more than three times daily. Regular eating practices and healthy food choices ensure individuals meet their nutritional requirements for growth and health maintenance [8]. About 85.6% had in-between meals, of which 69.2% had snacks, 11.2% had beverages and 8.8% had a full course meal. According to Gregory et al. (2010) [13] the consumption of snacks is a worldwide issue among children and adolescents regardless of where they live, whether in urban or rural areas or in developed or developing countries. However, snacking is a key characteristic of a children’s diet, and it is not a bad practice on its own. Snacks, if chosen wisely, can contribute positively to nutrient intake. In another study, Hackett et al. (2007) [14] opined that snacks should provide one fourth to one third of the daily energy intakes for children [14]. Majority of the children (97.2%) had access to fruits and vegetables, with about 55.2% on frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables, while 26.4% consumed twice weekly. This showed that their mothers are aware of the benefits of micronutrients to their baby’s foods.

Food frequency of the respondents

Table 4 showed the frequency of food consumption of the respondents. A greater percentage, 36.8%, consumed cereals and cereal products on a daily basis. This showed that cereals constitutes the bases of food consumption of the respondents. Maize pap is one of the major cereal incorporated as complementary feeding and given to babies at 6 months of age by individuals of low socio-economic strata. Most times, milk, soybean, boiled eggs and/or sugar are added to enhance the nutrient content of the food. Other cereal based complementary foods included Cerelac and SMA gold. The children are also introduced to foods eaten at home that normally go down well with the cereal, such as beans, moi-moi and akara with pap, rice; jollof, white with stew etc. These meals contain higher energy than the infant formular and help get the children acquainted with the meals prepared at home. Another food group mostly consumed by the children was starchy roots and tubers, evidenced by 39.2% on a consumption basis of three to four times weekly. Roots and tuber crops mainly consumed are mashed potatoes, yam, pounded yam and cassava products such as semovita etc. Some low income families introduce garri to their children which is normally cooked until it gels and given with soups such as okro, ogbono and vegetable soups. Cereals and starchy roots and tubers provide the needed energy for daily activities. Previous study by Ajao et al., (2012) [15] on influence of family size, household food security status, and child care practice on nutritional status of under- five children in Ile-Ife, Southern Nigeria showed that the energy food and body building food forms the bulk dietary intake (45% and 38% respectively) while protective and refined foods were consumed in small quantity (about 8% and 9%).

Legume products are consumed by almost half of the respondents (42.8%). They contain protein of low biological value which are also essential for growth and development of the young child. The most frequently consumed legumes were beans and soybeans. Soybeans contain protein of low biological value and it is being added to pap, cerelac and other formular for the children. Beans were also consumed mainly in mashed beans porridge, akara, moi-moi, and boiled rice with beans. Beans, groundnuts and soya beans are good sources of protein and cheaper than animal products. The respondents purchased more of these as a result of their poor socio- economic status and the rigid economy of the nation. A second reason is that soybean has a variety of usage and is regarded as the “magic food”. Previous studies reported that children consume vegetables mostly in soups and stew prepared at home than in-between meals [12]. With respect to vegetables, tomatoes, onion, pepper, green leafy vegetable, garden eggs and okro were consumed on a daily basis by almost all the respondents mainly in soups, stews and sauces as accompaniments to staple dishes like wheat meal, gari, cooked cereals, tubers and plantains.

Fruits and vegetables are good sources of vitamins, minerals and fiber. Vitamins help to build the body’s immune system in order to fight diseases and infections. They also assist metabolism of nutrients and can be converted to amino acids for use by the body (niacin to tryptophan). Watermelon, pineapple, banana and pawpaw were consumed by respondents on weekly basis. Because some fruits are seasonal, mangoes, avocado pear and local pear were consumed occasionally. The children consumed fruits regularly because of the knowledge of its nutritional benefits their mothers possessed. Frequency of nuts and seeds consumption showed that the children consumed lesser quantities throughout the week, evidenced by only 8.0% daily consumption, 14.8% three to four times weekly and 29.6% once to twice weekly. Nuts contain omega 3 fatty acids which help in brain development, and for healthy blood vessels.

The responses obtained from eggs, meat and poultry revealed that eggs, meat, and frozen fish were the main sources of animal protein consumed daily by most of the children. This is evidenced by a consumption rate of 38.0% three to four times weekly and 37.2% on a daily basis. These were mainly consumed in soups, stews, rice as well as eggs used in preparing breakfast for the children and lunch packs in school. Eggs, meat and poultry are good sources of protein of high biological value. They are good for growing children since they contain the essential amino acids needed for good health. One hundred and eight (43.2%) of the respondents consumed fish and fish products on a daily basis, 84 (33.6%) three to four times weekly and 17.2% once to twice every week. This is quite encouraging since fish is one of the most important protein sources in our diet. It contain both omega 3 and omega 6 fatty acids which help to combat pro inflammatory substances such as cytokines, prostaglandins and the eicosanoids.

The response obtained from milk and milk products consumption showed that 24.8% consumed milk products daily, 36.8% three to four times weekly and 16.4% once to twice in a week. This is quite encouraging and could be attributed to the fact that there is adequate knowledge of the nutritional benefits of milk. Secondly, the economic condition of the families were high which made it possible to provide such for their children. Most of the milk consumed by the children below 12 months were Peak 123, Pre-Nan and Nutri Start 2. Among the fats and oils, palm oil and refined vegetable oils were the most frequently consumed. About 79.2% of the children consumed fat and oil products daily. This is encouraging since fats improve the palatability of food, improves heart health and contributes the highest energy in the body. Palm oil was used mainly in soups and also served as an accompaniment to cooked beans. This is encouraging since palm oil is a rich source of pro-vitamin A which is crucial for vision and maintaining healthy cells, especially skin cells.

Nutritional status of the under 5 children by sex

Child malnutrition occurs when a child’s intake of nutrients (fat, protein, vitamins and minerals, etc.) is insufficient to sustain the needs of her body. Childhood malnutrition persists as a public health problem in developing countries. It is estimated that less than 5% of children in developing nations are wasted [16]. The main factors associated with stunting in the study were: sex of the child, wealth index and geopolitical zone. Akombi et al. (2017) [7] reported that the factors associated with severe stunting included: sex of the child, wealth index, geopolitical zone and maternal BMI. In this study, we observed that male children had a significantly higher risk of being stunted and severely stunted than their female counterpart. The prevalence of wasting in the current study is a little above this estimate. The current study indicates that 8% of the study population was stunted and this falls within the WHO estimate for developing countries [16]. The prevalence of underweight, stunting, and wasting from this study is lower than what was reported by Manjunath et al. (2008) [17]. It is also consistent with the estimate from the 2013 national demographic and health survey, except for stunting [18]. Stunting in this population is lower than the national estimate. Stunting and underweight in the current study is slightly lower than the prevalence in South Eastern Nigeria. However, the prevalence of wasting reported by Ezeama et al. (2015) [19] (18.1%) from south eastern Nigeria is higher than prevalence in the study population (7%). The Government should sustain and scale up existing interventions that will reduce malnutrition. Prevalence of PEM is 1.2%. This is lower than the prevalence reported by Andy et al. (2016) [20].

Several factors are associated with PEM and vary from place to place. According to Andy et al. (2016) [20], the prevalence of PEM among male children is higher than in female children and the relationship between PEM and gender is statistically significant. This finding is similar to that obtained from the present study and the position of Ubesie et al., (2012) and Yalew (2014) [21,22]. This underlines the need to give special attention to mothers of male children when counselling women about the nutrition of their children. This gender based health inequality may be as a result of community specific cultures in Nigeria which reflect a historical pattern of preferential treatment of females due to the high value placed on women’s agricultural labor [23]. Also, male children tend to be more physically active and expend large amounts of energy which should have been channelled into increasing growth. On the other hand, females are culturally expected to be less active and stay at home with their mothers near food preparation. This finding is consistent with results from other cross-sectional studies carried out in Kenya [24], Tanzania [25] and Ghana [26]. In Jayatissa (2012) [27] study on assessment of nutritional status and associated factors; there were no consistent differences between sexes regarding occurrence of stunting but a higher prevalence of wasting and underweight was seen among males. The MUAC also shows that 1.78% males and 0.72% females were malnourished. Akorede and Abiola (2013) [28] stated that since the present condition (nutritional status) have a lot of effect on the future then adequate care should be given to the children at that tender age [29-36]. The best way to achieve optimal nutritional status is to improve on the socioeconomic conditions of children and teach nutrition education to mothers, most especially on the best practices to care for their children.

Conclusion and recommendation

This study shows that stunting, underweight and wasting results from a complex interaction of factors. Hence at the individual level, interventions to prevent stunting, underweight and wasting should focus on improving women’s nutrition and education to reduce low birth size, improve household hygiene and promotion of appropriate complementary food and feeding practices. Poor Socioeconomic and environmental conditions are important determinants of nutritional status. Educated and employed mothers have control over the purchase of the dietary items and will be more qualified and capable of taking care for their children properly. Mothers should be adequately educated on how best to imbibe nutrition knowledge to the care of their baby so as to reduce child malnutrition in Imo State. Education of women should be treated with utmost priority because it will help raise the standard of living of the family and pave way for a better socio-economic status. Government and nutrition policy makers should enact policies that will enhance food security, and promote programs like operation feed the nation, food bank and cash remission. Further research can be carried out on the above study, more especially in the Northern parts of the country where child malnutrition has wrecked much havoc.

To read more about this article: https://irispublishers.com/gjnfs/fulltext/prevalence-of-malnutrition-and-stunting-in-under-five-creche-of-a-rural-private-school.ID.000561.php

For more Open Access Journals in Iris publishers please click on: https://irispublishers.com/pdf/peer-review-process-iris-publishers.pdf